Empires of the Silk Road: A

1) Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present – Christopher I. Beckwith

Princeton University Press | 2011 | PDF

The first complete history of Central Eurasia from ancient times to the present day, Empires of the Silk Road represents a fundamental rethinking of the origins, history, and significance of this major world region. Christopher Beckwith describes the rise and fall of the great Central Eurasian empires, including those of the Scythians, Attila the Hun, the Turks and Tibetans, and Genghis Khan and the Mongols. In addition, he explains why the heartland of Central Eurasia led the world economically, scientifically, and artistically for many centuries despite invasions by Persians, Greeks, Arabs, Chinese, and others. In retelling the story of the Old World from the perspective of Central Eurasia, Beckwith provides a new understanding of the internal and external dynamics of the Central Eurasian states and shows how their people repeatedly revolutionized Eurasian civilization.

Beckwith recounts the Indo-Europeans’ migration out of Central Eurasia, their mixture with local peoples, and the resulting development of the Graeco-Roman, Persian, Indian, and Chinese civilizations; he details the basis for the thriving economy of premodern Central Eurasia, the economy’s disintegration following the region’s partition by the Chinese and Russians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the damaging of Central Eurasian culture by Modernism; and he discusses the significance for world history of the partial reemergence of Central Eurasian nations after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

2) Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane – S. Frederick Starr

Princeton University Press | 2015 | PDF

In this sweeping and richly illustrated history, S. Frederick Starr tells the fascinating but largely unknown story of Central Asia’s medieval enlightenment through the eventful lives and astonishing accomplishments of its greatest minds–remarkable figures who built a bridge to the modern world. Because nearly all of these figures wrote in Arabic, they were long assumed to have been Arabs. In fact, they were from Central Asia–drawn from the Persianate and Turkic peoples of a region that today extends from Kazakhstan southward through Afghanistan, and from the easternmost province of Iran through Xinjiang, China.

Lost Enlightenment recounts how, between the years 800 and 1200, Central Asia led the world in trade and economic development, the size and sophistication of its cities, the refinement of its arts, and, above all, in the advancement of knowledge in many fields. Central Asians achieved signal breakthroughs in astronomy, mathematics, geology, medicine, chemistry, music, social science, philosophy, and theology, among other subjects. They gave algebra its name, calculated the earth’s diameter with unprecedented precision, wrote the books that later defined European medicine, and penned some of the world’s greatest poetry. One scholar, working in Afghanistan, even predicted the existence of North and South America–five centuries before Columbus. Rarely in history has a more impressive group of polymaths appeared at one place and time. No wonder that their writings influenced European culture from the time of St. Thomas Aquinas down to the scientific revolution, and had a similarly deep impact in India and much of Asia.

Lost Enlightenment chronicles this forgotten age of achievement, seeks to explain its rise, and explores the competing theories about the cause of its eventual demise. Informed by the latest scholarship yet written in a lively and accessible style, this is a book that will surprise general readers and specialists alike.

3) Warriors of the Cloisters: The Central Asian Origins of Science in the Medieval World – Christopher I. Beckwith

Princeton University Press | 2012 | PDF

Warriors of the Cloisters tells how key cultural innovations from Central Asia revolutionized medieval Europe and gave rise to the culture of science in the West. Medieval scholars rarely performed scientific experiments, but instead contested issues in natural science, philosophy, and theology using the recursive argument method. This highly distinctive and unusual method of disputation was a core feature of medieval science, the predecessor of modern science. We know that the foundations of science were imported to Western Europe from the Islamic world, but until now the origins of such key elements of Islamic culture have been a mystery.

In this provocative book, Christopher I. Beckwith traces how the recursive argument method was first developed by Buddhist scholars and was spread by them throughout ancient Central Asia. He shows how the method was adopted by Islamic Central Asian natural philosophers–most importantly by Avicenna, one of the most brilliant of all medieval thinkers–and transmitted to the West when Avicenna’s works were translated into Latin in Spain in the twelfth century by the Jewish philosopher Ibn Da’ud and others. During the same period the institution of the college was also borrowed from the Islamic world. The college was where most of the disputations were held, and became the most important component of medieval Europe’s newly formed universities. As Beckwith demonstrates, the Islamic college also originated in Buddhist Central Asia.

Using in-depth analysis of ancient Buddhist, Classical Arabic, and Medieval Latin writings, Warriors of the Cloisters transforms our understanding of the origins of medieval scientific culture.

4) Inside Central Asia: A Political and Cultural History of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz stan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Iran – Dilip Hiro

The Overlook Press | 2011 | PDF

The former Soviet republics of Central Asia comprise a sprawling, politically pivotal, and richly cultured area of the world. Given the strategic location of this region, its predominantly Muslim population, and its valuable resources, it is not surprising that this vast expanse of Eurasia is emerging as an influential and coveted area. For India, which has deep cultural and historical links with the region-Babur, incidentally, was from Central Asia-this is an intriguing, fascinating and educative look at a part of the world that is of great importance to it. Since their political inception during the rule of Joseph Stalin, these countries have experienced tremendous socio-political change. The growth of oil wealth, the arrival of Western tourists and businessmen, and the scramble for influence by the US, China and Russia, have altered their economic and political landscape. Despite this, the spirit of Central Asia has remained untouched at its core. In this comprehensive, up-to-date survey, renowned political writer and historian Dilip Hiro offers an account that places the present-day politics, economics and peoples of Central Asia and neighboring Turkey and Iran in an international context. It is a detailed portrait of a region which has, throughout history, influenced and been influenced by India.

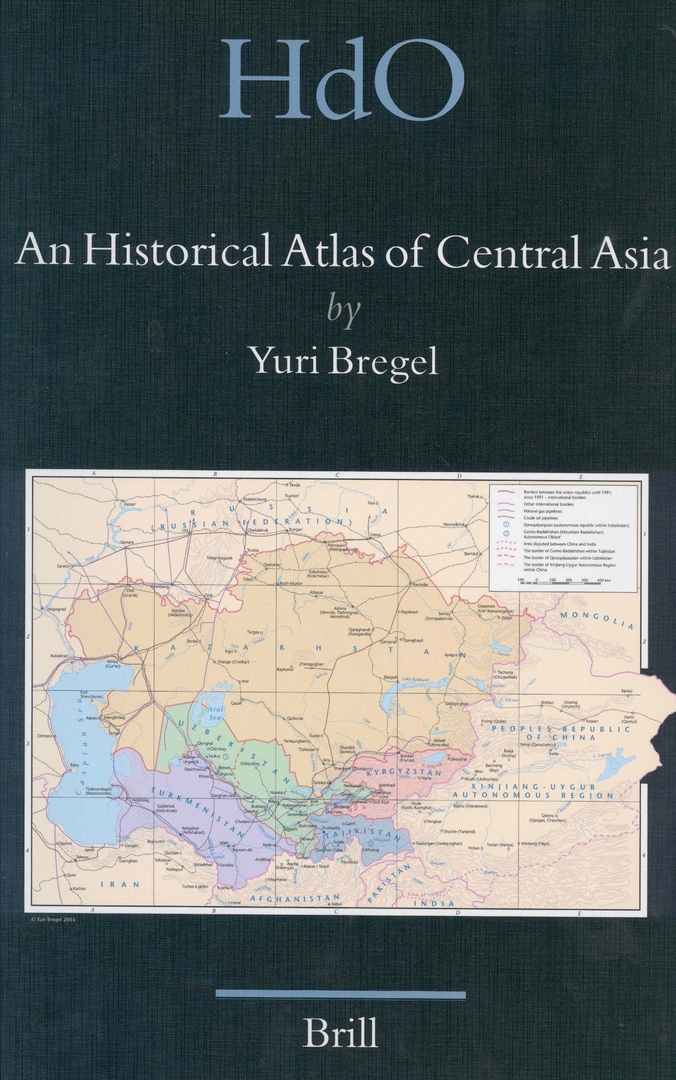

5) An Historical Atlas of Central Asia – Yuri Bregel

Brill | 2003 | PDF

Yuri Bregel’s Atlas provides us with a bird’s eye view of the complicated history of this important part of the Islamic world, which is closely connected with the history of Iran, Afghanistan, China, and Russia; at different times parts of this region were included in these neighboring states, and since 1991 five new independent states emerged in Central Asia: Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Covering the 4th century B.C. to the present, the maps show the various political entities, their approximate borders, the major ethnic groups and their migrations, military campaigns and battles, etc.

Each map is accompanied by a text which gives a concise survey of the main events of the political and ethnic history of the respective period. With special maps on the distribution of the Turkmen, Uzbek, Qazaq, and Qirghiz tribes in the 19th-20th centuries, as well as the location of major archaeological sites and architectural monuments. The last map (Central Asia in 2000) shows existing gas and oil pipelines.

1 / 5

1 / 5 2 / 5

2 / 5 3 / 5

3 / 5 4 / 5

4 / 5 5 / 5

5 / 5